Digital interventions to mitigate the spread of Covid-19 have attracted great amounts of interest and controversy. In this post, I'll examine the interaction of technology and English law in the case of presence tracing — interventions designed to enable those who were co-present to someone later deemed to have been an infection risk to test, self-isolate, or take other action.

Proximity v Presence Tracing

Presence tracing refers to a form of contact tracing based on whether two individuals were co-present in a venue where an infection could have been transmitted. It is especially important where a disease may be airborne or transmitted through contaminated objects or surfaces (fomites). In the case of Covid-19, it complements proximity tracing, a form of contact tracing based on whether two individuals were near each other in a context and for a duration conducive to disease transmission.

Both presence tracing and proximity tracing can be manually carried out through learning the identities of individuals to contact who were proximate or co-present to an individual who is or was infectious. This might take the form of referring to contact details held by a venue, contact details obtained from an interviewee, or indirect identification through investigative methods such as those based on transaction or CCTV data.

Both can also be facilitated in more automated manners through digital technologies. In all nations of the UK,[1] proximity tracing is supported through a decentralised Bluetooth protocol implemented by American smartphone duopolists Apple and Google called Exposure Notification, based in part on the DP-3T protocol designed by European universities.

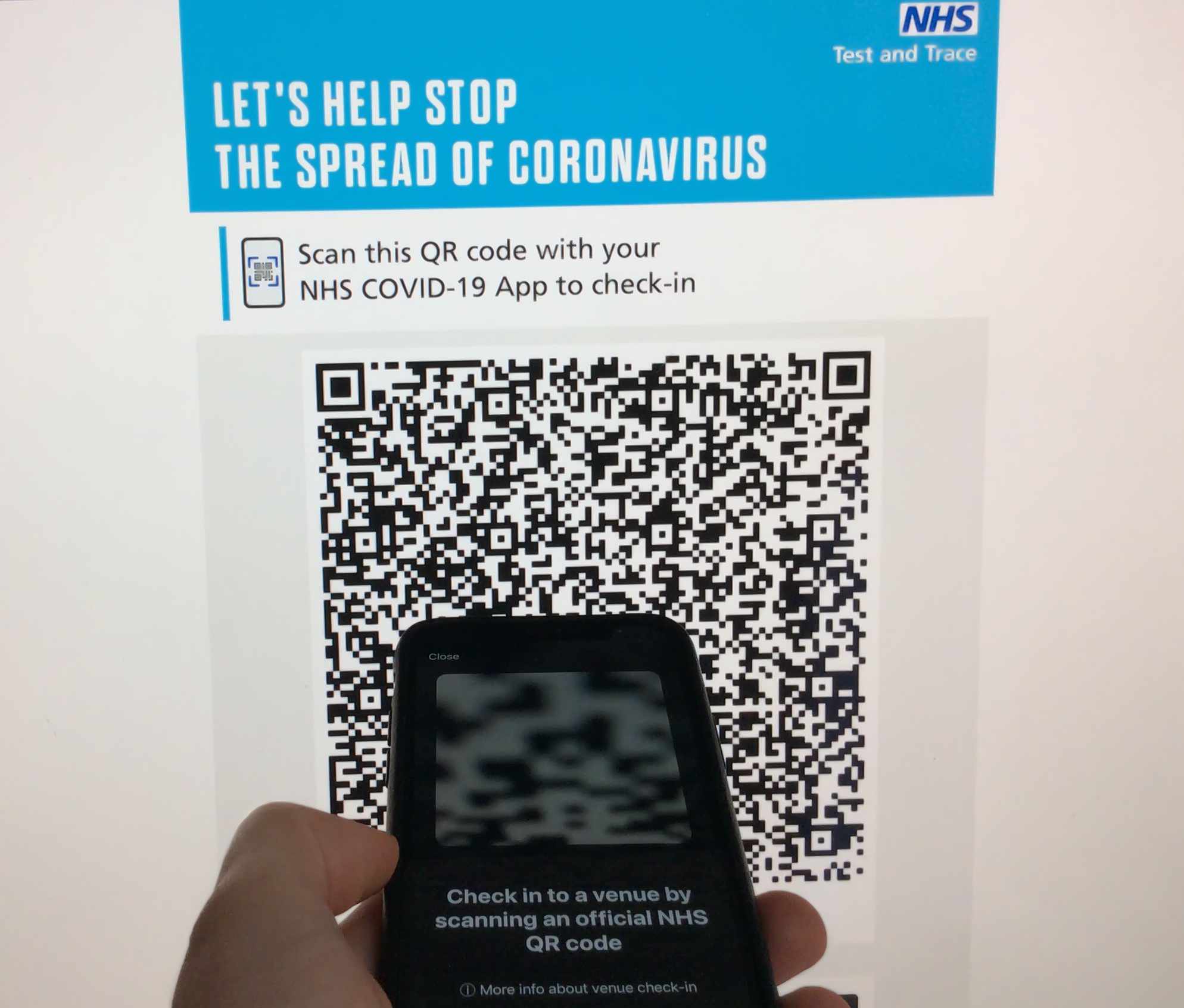

The collection of contact details by venues for use in manual presence tracing can be supported digitally. Many companies sold platforms or technologies for venues to be used in place of paper and pen, with some proving controversial as providers were accused of repurposing the data collected. Individuals were often faced with opt-in and opt-out boxes of various degrees of legality which might lead them to marketing or be subject to data sharing they did not want. Some governments, such as Scotland's, have produced apps (Check In Scotland) which are effectively little more than government-run third party contact collection tools. All these tools typically use QR codes, a robust type of barcode widely scannable by devices with cameras that can contain a small amount of arbitrary information like a URL, identifiers, or a cryptographic signature.

Data collection tools create privacy risks, but also a bottleneck to obtain and filter the data and reach out to those concerned. England and Wales' NHS Covid-19 app instead has a function that uses QR codes to notify individuals of their historical co-presence at a risky venue, without collecting their details. The protective nature of this difference is the source of many of the legal tensions that we will see below.

The NHS Covid-19 app may have been the last app to launch in the United Kingdom, but additionally incorporated a digital presence tracing system from its first nationally available version. It functions as follows:

- A printable QR code poster is generated by a venue after providing their name and contact details to an NHSX website. This QR code contains information which can be used to identify the venue on an NHSX server.

- A user can scan a poster. Their device will display some information embedded in the poster (eg name and address of venue), and they can confirm. This information, along with the time of the scanning, is stored on their device for up to 21 days. It does not leave the device, and users can manage their scanned venues and choose to erase them.

- If a public health authority determines that a particular venue (for example, on the basis of a manual contact tracing interview) presented risks to individuals worthy of notification, they are able to broadcast an identifier of the venue's to individuals' devices.

- Individuals' devices download these lists, and if a match within a given timeframe is found, the device notifies the user with further instructions (without providing the name of the triggered venue). The device does not automatically communicate any information to a public health authority.

While a formal analysis or protocol has not been published by NHSX, this system appears intended to provide the following protective properties to all users, regardless of whether they check-in, are notified, or test positive for Covid-19:

- Venues do not receive any information about users that visited them.

- Central authorities do not receive information about where users of the app visited.

- Only the user learns they received a notification or instruction (as the risk is calculated on the phone)

It can be characerised as a 'decentralised' presence tracing approach, as the risk calculation and notification takes place not on a central server, but on individuals' devices.

(Note: More detailed and formal statements of the properties of similar system to the England and Wales approach can be found in our CrowdNotifier White Paper — however note that the protocol is not identical, but provides more extensive protection than the NHSX approach in some areas, such as against the triggering of illegitimate notifications against particular venues by central actors designed to eg suppress certain populations.)

The English legal framework for presence tracing

Legal frameworks in England and Wales have been made around this system. I will focus predominantly on the English law, but the situation is very similar in Wales.

In England, provisions supporting presence tracing are laid out in The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Collection of Contact Details etc and Related Requirements) Regulations 2020 (the 'Regulations'), a statutory instrument made under the Public Health (Control of Disease) Act 1984. This instrument places obligations on relevant premises (which I have been calling venues for short) to facilitate presence tracing.

In parallel with the launch of the app in late September 2020, regulation 6 of the Regulations sets out an obligation for a person responsible for a listed service or activity to display a QR code in the premises occupied or operated for the purpose providing this activity.

Requirement to display QR Code

6.—(1) A relevant person must in an appropriate place display and make available a QR Code at relevant premises that they occupy or operate with a view to achieving the aim in paragraph (2).

(2) The aim is to enable an individual who seeks to enter the relevant premises in a case set out in regulation 9 and has a smartphone in their possession to scan the QR code with that smartphone as, or immediately after, they enter the premises.

Listed services are detailed in the schedule to the regulation, and can be summarised to include hospitality services, leisure and recreation services and 'close contact' services (eg hairdressers), but in general omit places where an individual might be found regularly, such as a workplace or university, and omit retailers other than those considered 'close contact' services.

The Regulations place an obligation on these premises to request that all individuals aged 16 or over entering them either provide their contact details manually, or scan the QR code. Before the end of March 2021 when they were amended, the Regulations allowed an individual to manually sign in on behalf of a group of up to six, but still required app users to sign in individually. The Government incorrectly characterised these changes in its guidance and annoucement, which appeared to indicate that the need for individuals to all sign in with the app separately, if they chose to use it, was new, when it had always been the case since obligations to place QR codes had been active.

The Digital Divide — To Scan or Not To Scan?

The structure of the Regulations is therefore such that there is a requirement to collect data manually which is only waived in the case of the scanning of an official QR code (which is also an obligation to display). It might appear at first glance that no-one is unfairly disadvantaged by not possessing (or choosing to use) a smartphone or the NHS Covid-19 app. On closer inspection however, there are some important differences.

Privacy

Individuals who choose to use the app to enter a venue benefit from certain privacy protections of the system. Perhaps the most obvious benefit is that the venue (or anyone that it passes data to) is unable to use or misuse the contact information of those individuals. Some reports indicated cases of suspected misuse of such information, such as bar staff making unwanted advances on patrons by locating them on messaging services. Where an individual is worried about surveillance by public bodies, the QR code system as implemented does not allow a public authority to approach a venue and see which individuals has visited. Unlike a manual list, which could be consulted in this manner, this NHS Covid-19 app onlys allow a venue to be triggered and notify everyone who scanned the identical QR code at the relevant time.

For the purposes of these aspects of privacy, individuals are therefore more protected when they use the app.[2]

Mandatory Quarantine

A further important difference is only apparent when reading these Regulations in combination with The Health Protection (Coronavirus, Restrictions) (Self-Isolation) (England) Regulations 2020. Regulation 2 of this instrument places self-isolation obligations on individuals meeting certain conditions. However, these obligations only apply to adults notified 'other than by means of the NHS Covid 19 smartphone app developed and operated by the Secretary of State'. (A differently structured exemption with the same effect also exists in The Health Protection (Coronavirus Restrictions) (No. 5) (Wales) Regulations 2020 reg 5.)

Why is this? One reason may be the potential enforceability of such a provision. The NHS Covid-19 app may generate notifications both based on the Bluetooth 'exposure notification' system and, separately, the presence tracing system. Both of these systems as deployed in England and Wales do not identify the users who have been notified to the public health authority. They are technically capable of doing so (if eg a user registers a phone number to pass on when the phone calculates they are at risk), although Apple and Google both prohibit user data being passed on in this situation without consent, and require the app to function as a notification tool without mandatory identification upon notification - else they may prohibit its distribution through the private regulatory bottleneck of their app stores (eg Apple, para 3.1). It is worth noting that the platforms used this power in April 2021 against England and Wales, preventing them from integrating a feature that would upload visited venues of individuals who tested positive. Users can delete the application (and in the case of proximity tracing, clear collected Bluetooth keys from their operating system) and there will be no evidence (short of extremely intricate forensic data recovery) that they were notified. As a consequence, attempts to enforce or prosecute on the basis of this provision will prove extremely difficult.

Concerns that app users dealt notifications could 'ignore such information with impunity' were raised by the House of Lords Secondary Legislation Scrutiny Committee on 8 October 2020. The Department of Health and Social Care, responding to concerns of discrimination (potentially on the basis of age) that those without the app would be more likely to be fined than those with the app stated that there would be no such discrimination, because all individuals were liable to be notified through manual contact tracing, creating legal obligations on them. Something that, to my knowledge, was not picked up by the Committee or in the debate on the issue in Hansard is that this logic only works when considering proximity tracing, not presence tracing.

Users of the Bluetooth proximity tracing part of the NHS Covid-19 app supplement the manual contact tracing system by both rendering themselves susceptible to notification they may not otherwise have received (eg an anonymous person opposite them on a train) as well as providing routes to notify others in that situation, should the user test positive. As a Test and Trace official would not know whether an individual described as encountered in a contact tracing interview was an app user, they would be contacted with the same propensity as an individual who was not an app user — rendering the DHSC's logic correct. However, in relation to presence tracing, the QR code is a replacement. A user of the app will not be contacted in relation to a risky venue by a manual test and trace system, because they did not leave their details. Consequently, there is a discrimination risk in relation to the distribution of alerts provided.

(An alternative justification for an app exemption, not mentioned in debates or by the DHSC, relates to how a proximity tracing app may trigger false positives, eg based on a neighbour with thin separating walls, or a job where an individual is wearing full PPE or protected by an effective plastic screen. However, this logic only applies due to the Regulations not distinguishing between a proximity notification and a presence notification — in all cases, a presence notification will be based on a validated scan, and the same public health judgement as to whether the venue posed a risk to somebody who entered at a particular time.)

Isolation Payments

A small footnote is worth dedicating to a now largely irrelevant difference between digital and non-digital notifications. Individuals who were notified of a presence tracing risk through the app were initially not eligible for means-tested £500 self-isolation compensation (as a matter of policy rather than law). While the Secretary of State claimed that accessing compensation through the app was as easy as pressing a button, a fortnight later the Government admitted that such a button did not exist, but 'will come'. Without this button, there was no mechanism to prove a notification. Guidance now exists on the NHS website on how to claim a payment if notified by the NHS Covid-19 app.

Conclusion

In some ways, this historical discussion is empirically irrelevant. Software developer Russ Garrett has monitored how many risky venues have been published, illustrating that fewer than 300 venue alerts have been sent in five months of operation — a period which has seen over 3,000,000 confirmed positive cases in England. However, Rowland Manthorpe (Sky) reported that this was largely related to capacity issues in the Test and Trace system, but that a leaked document indicated a significant centralisation of a venue assessment process, indicating it may play an important role as restrictions are eased in 2021. Furthermore, many other countries have developed such apps, such as the Swiss NotifyMe app or the German CoronaWarnApp, both based on the CrowdNotifier system, with legal frameworks and considerations around presence tracing likely to develop further internationally in the future.

What lessons can be taken from this? Ultimately, creating mandatory legal requirements alongside digital technologies respectful of privacy can lead to some quite nuanced challenges to ensuring that individuals who choose not to use a technological intervention are treated similarly. Digital technologies can provide heightened privacy compared to manual approaches, but these technologies may — by design — lower the potential for enforcement or coercion. This situation has the distinct flavour of a technical approach fitting hastily into a legal framework being designed separately. In some countries, such as Germany, this trade-off does not currently exist because there is no exemption to providing manual contact details for people who scan in with QR code, either through the Federal government's app, the CoronaWarnApp, or through private providers such as Luca (see eg GVB 562 (23 June 2020) s 3). In all cases, by instead considering legal and technical, requirements together at an earlier stage, less arbitrary trade-offs may be possible.

Note: This post refers to legislation as it was on 27 April 2021.

The UK has three separate apps for proximity tracing. Northern Ireland's StopCOVID NI was launched on 31 July 2020, Scotland's Protect Scotland app launched on 10 September 2020, and England and Wales' NHS Covid-19 app launched on 24 September 2020. While all three integrate similar Bluetooth-based functionality for proximity tracing, and have informational functions and abilities to request and integrate with tests, the England and Wales NHS Covid-19 app additionally incorporated a presence tracing system based on QR codes. This addition was based on the codebase of the New Zealand NZ Covid Tracer app, released 20 May 2020, although the functionality differs. ↩︎

Further technical analysis of privacy and presence tracing can be obtained from reading the CrowdNotifier protocol, of which I am a co-author, used in Switzerland and Germany. It has further abuse protections that the NHS Covid-19 app does not have, but in relation to privacy of users functions it similarly to how it appears the NHSX app is intended to function. ↩︎